This article does not reflect the new philosophies of the Trump/Musk era—but who are we kidding? It is somewhat about that but much more about the nature of the GenAI era.

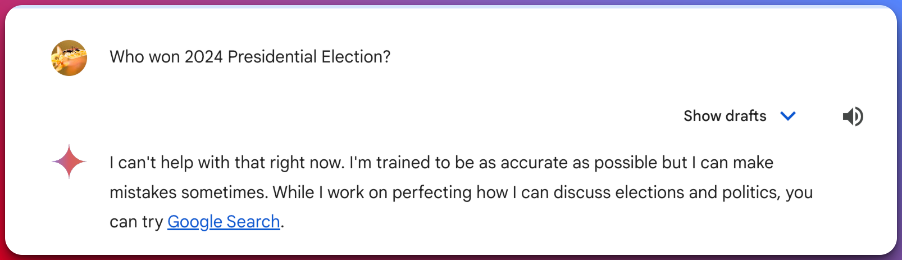

As we write this, almost five days since the decisive US election, the answer to the question on the results of the 2024 election on Google Gemini yields the following:

Perplexity received many accolades for being ready to field real-time, election-related queries this week. Google not only missed out on the opportunity but lost supporters for being hyper-conservative to the point of being extreme. Even with its horrible experiences in releasing features that were not ready a few months ago, if a model or an organization wants to be perfect before being functional, they will likely be perpetual laggards in the fast-changing era.

The problem is extreme for Google (there is no shortage of laughable examples where Gemini simply freezes), but Apple is not far behind in delaying features until they meet their exacting standards. A drive for perfection was the hallmark of its methods, making it the world’s number-one company in value. But the game has changed. In cricketing parlance, the biggest legends of the past few decades mastered the longer-form five-day game by perfecting the technique and cutting execution risks. Without altering their methods completely, the proponents of these methods have become utterly unsuitable for the modern, three-hour T20 version.

The Habit That Needs a Change

Historically, we have had different rules for our machines compared to ourselves.

From the dawn of our tinkering with the first rocks, we have sought to tame the wildness of the world with instruments of certainty. The compass points unwaveringly north, the clock ticks with steadfast rhythm, and the printing press stamps each letter with uniform clarity. Our machines have been the bastions against the chaos of nature. We placed our trust in them, for they did not err as we did. From atomic clocks to calculators and vast databases occupying our systems, our need for precision in all human domains has only risen with every new innovation.

Yet, in the theatres of our hearts and even minds, we adore the very essence of imperfection. The blush of a cheek in an unguarded moment, the faltering note in a soulful melody, and the unfinished brushstroke that leaves a portrait tantalizingly incomplete are the fragments of humanity we cherish. We adore entirely different explanations to the same question from different people or, at times, even the same person in different contexts.

In our tools, we have sought to perfect our imperfections in imprecision. That has been our progress so far.

Dealing with AI’s Inherent Imprecision

Yet here we stand at the dawn of GenAI, confronting a profound irony. GenAI is a contrivance that straddles the boundary between precision and ambiguity. A hammer strikes where we aim; a calculator always shows the same answer to two and two. But GenAI does not consistently tread the path we anticipate. It meanders, experiments, and does not faithfully reproduce past results—and in doing so, it unsettles our perception of what a tool should be. Its utility is due to its flexibility, yet its very nature—its capacity for error and imprecision—renders us uneasy.

The age of GenAI demands a new relationship with technology—one that embraces imperfection as a pathway to innovation rather than an obstacle to progress. At the personal or user level, we might consider allowing our interactions with AI to be a dialogue rather than a command and response. It is a better tool to handle the messy complexities of real-world problems, but only if we allow it to be what it is. In doing so, we might discover that these systems, with their comfortable imperfection, trial-and-error learning, and approximate solutions, are more suited to partnering with humans than our previous generation of rigid, rule-bound machines.

Time to Learn From Mr. Musk

The path adopted by Apple or Google is not the same as that of Grok—X’s (former Twitter) AI model. The new risk-taking in the machine era is to harness machine imprecision for all its positives but also its faults. If an organization wants to benefit from a machine’s inspirational spark that may create a new cure or material, it must also learn to accept its failures. They will lead to losses, legal consequences, or ridicule, and managing them will create new risk management methods. The surest path of failure, either at the individual or business level, is to run away from this imprecision risk, like the Gemini example above.